Investigating Infrastructure Links with Passive DNS and Whois Data

I am republishing here the guide on using passive DNS and Whois data in investigation that I published earlier this year on the Amnesty Citizen Evidence Lab website.

Many disinformation or malware campaigns rely on a computer architecture based on several servers and domains, and even if they often try to hide the infrastructure, it has to be accessible online. Investigating these infrastructure links is often a good way to get a broader view of the campaign. This is one of the tools we use in our investigations at Amnesty Tech.

In this guide we will look at how the Domain Name System (DNS), Passive DNS and Whois data are used to investigate an infrastructure.

Understanding DNS and Whois

The Domain Name System#

DNS is one of the core components of the Internet. It allows a computer to translate a domain name (like amnesty.org) into an IP address (like 123.45.67.89). Computer networks use IP addresses to communicate; any message on the network has a source and destination IP address and the network knows how to route the messages from the sender to the recipient. Because it would be difficult to remember an IP address, DNS was invented so that users can access information through easily-recognised domain names, which are then translated into the IP addresses that enable communication.

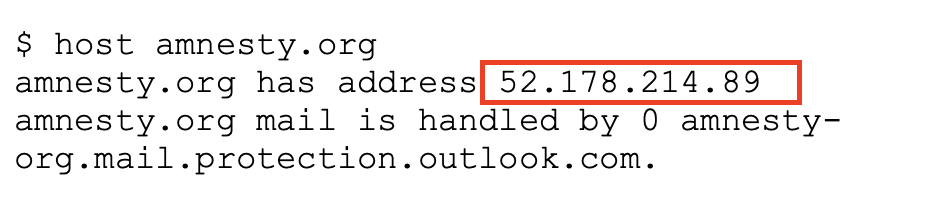

Let’s do a DNS resolution on amnesty.org. For this example, the Linux command host is being used, but you can use nslookup on Windows or an online tool like CentralOps.

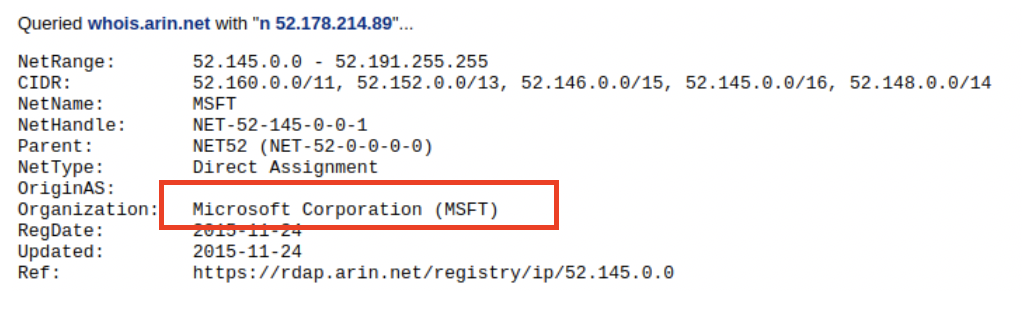

We can see here that the domain amnesty.org is hosted on a server with the IP address 52.178.214.89. Once we know the IP address, we can use tools like CentralOps or ipinfo.io to find out who owns the server (in this case, Microsoft).

Note that we are only using the IPv4 DNS record type here, which is a type of record called “A” in the DNS protocol, but there are many other types available, such as MX for mail servers or AAAA for IPv6. You can find a full list on Wikipedia.

Passive DNS#

DNS requests only give us the current link between the domain and the IP. We cannot easily find out which domains are hosted on a particular server, or see where a domain was hosted in the past. That’s where Passive DNS databases can help.

Passive DNS databases are based on passive records of DNS resolution over time. Different databases have been built specifically to gather that information, mostly (but not only) by commercial companies. For instance, OpenDNS is a company offering free DNS servers, and records the DNS resolutions in order to resell this information (they were acquired by Cisco in 2015).

Put simply, a passive DNS database is a large list of the historical links between domains and IP addresses.

Here is a list of some Passive DNS data providers that provide free, but often limited, access:

- RiskIQ: commercial service that offers community accounts limited to 15 queries a day (this is the service we are going to use in the example below)

- Security Trails: commercial service offering 50 queries a month for free

- Robtex: free service (but quite limited)

- Farsight DNSdb: provides access to community edition (programmatic API only, searches only cover the previous 90 days)

Whois Data#

When you register a domain name, you are asked to provide personal information, including an email address, a name, a phone number and a physical address. In the early days of the internet, this information was completely open, so that everyone could see who owned a domain name. With development over time, and an increasing awareness of privacy and security issues, this data has become more and more incomplete or hidden, either because users have provided fake information, or because it started to be protected The introduction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe has prohibited companies from publishing information that identifies individuals, making Whois data largely obsolete.

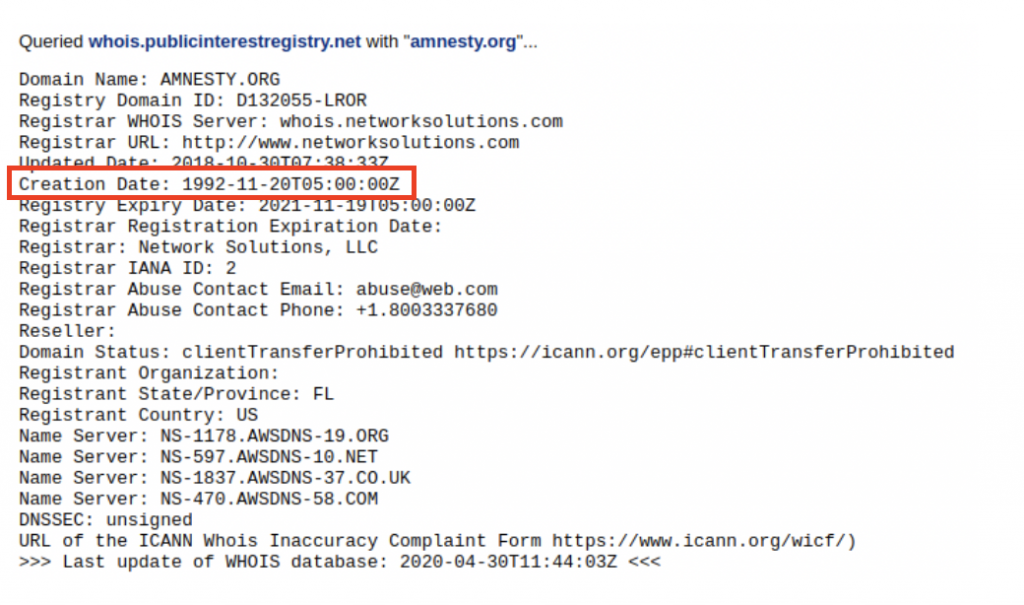

Going back to the Amnesty.org example, you can see the Whois data using CentralOps:

Whois data is still an interesting source of information for two reasons:

- It gives us an idea of when a domain was created, which is useful in creating a timeline of events. For example, we see above that amnesty.org was registered in 1992.

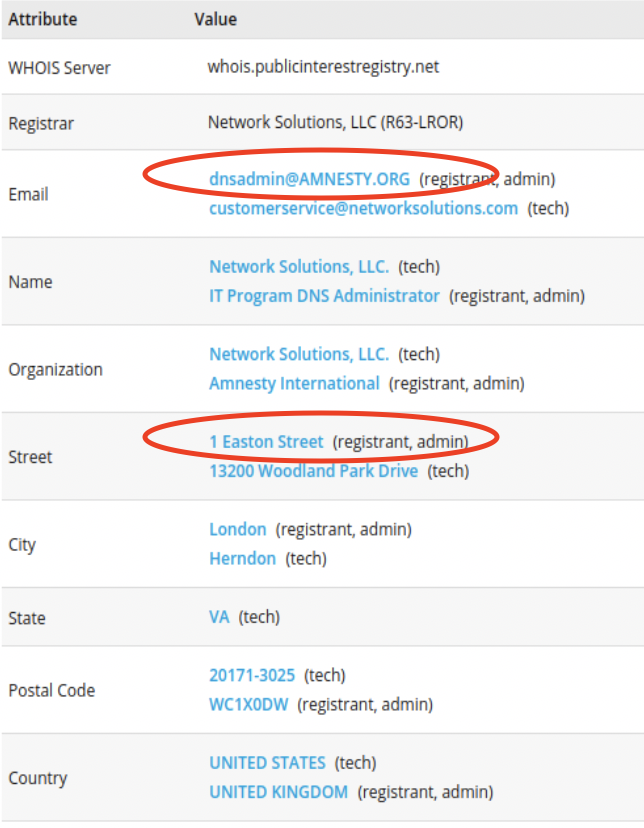

- Some Passive DNS providers include historical Whois information, and this often provides some interesting information for older domains such as name, address, phone number or email address. For instance, in RiskIQ we can see the Whois records of amnesty.org from 2013, which includes the Amnesty admin email address, and physical address:

How to use passive DNS investigation

Let’s see how to use Passive DNS data with an example from the malware and phishing campaign that targeted Human Rights Defenders from Uzbekistan in 2019. We are going reproduce here some of the steps we took during the investigation, using the community access to RiskIQ.

(Please note that the example here is just a small part of the infrastructure of this campaign as the operator used more than 70 domains and 20 servers.)

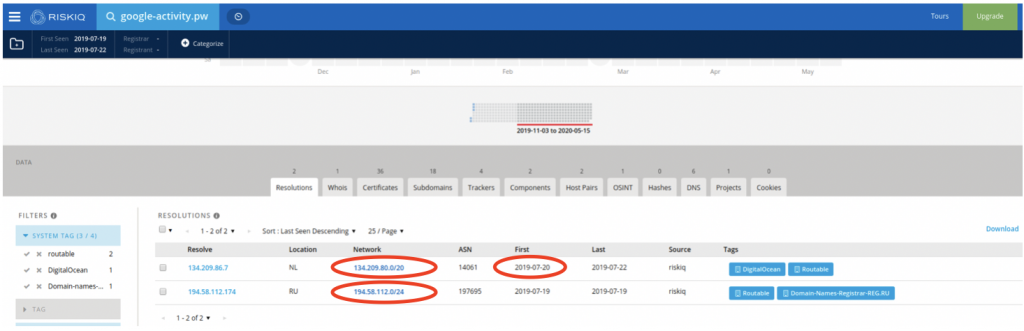

During the investigation we identified a domain (google-activity[.]pw) that we thought was related to the campaign. Let’s have a look at it in RiskIQ:

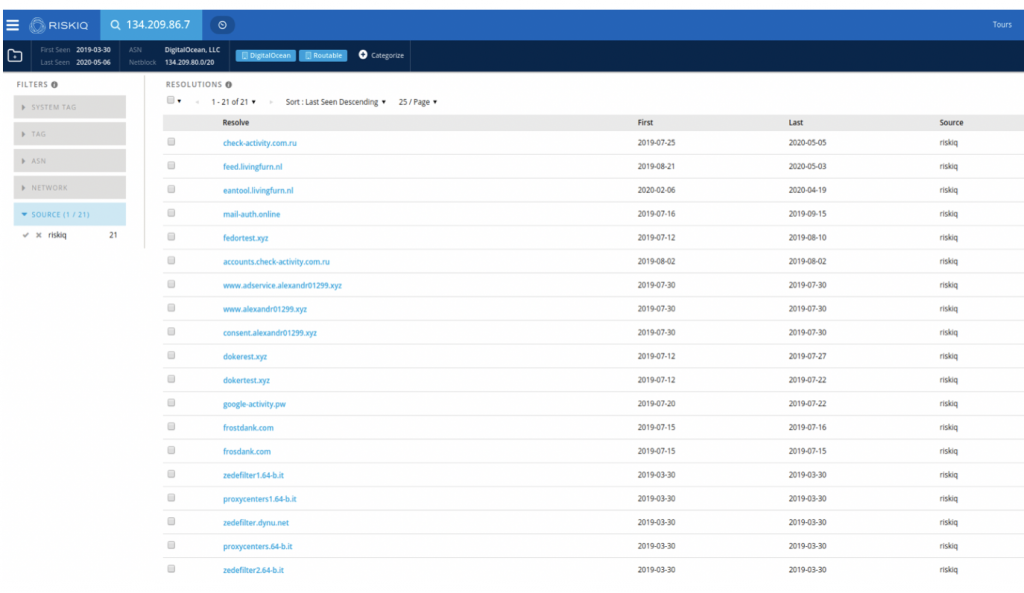

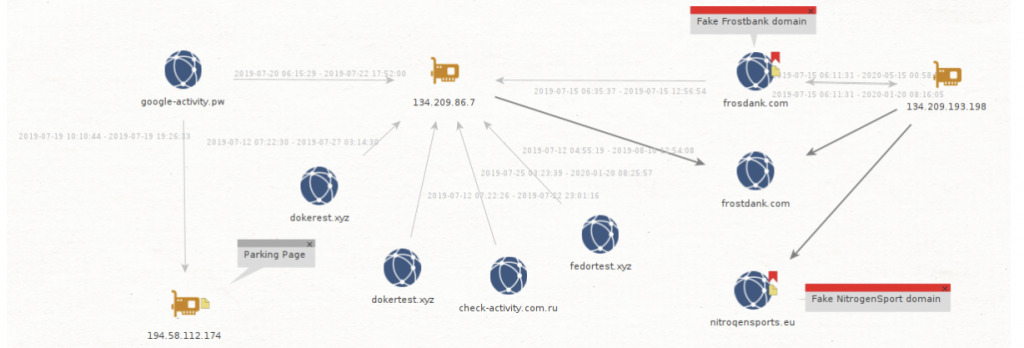

We can see that the domain first appeared in July 2019, and was hosted on two servers: 134.209.86[.]7 (a DigitalOcean server) and 194.58.112[.]174, which is actually a parking page for the reg.ru registrar. The latter IP is not very interesting as it would host a lot of parked domains not related to our investigation, but the first IP shows us more domains related to the same campaign:

We can see from the timeline of the domains that this server was likely to have had three different owners:

- Someone in March 2019, likely not related to our campaign (zedefilter1.64-b.it etc.) as the domains do not seem linked to any malicious activity and happened before our campaign started

- The campaign we are tracking is between July 2019 and likely August 2019 (check-activity.com[.]ru is still hosted on the server, but likely because it was not removed by the operator)

- A new owner from August 2019 (feed.livingfurn[.]nl and later eantool.livingfurn[.]nl)

Based on this analysis, we can identify 12 new domains related to this campaign:

check-activity.com[.]ru 2019-07-25 2020-05-05

mail-auth[.]online 2019-07-16 2019-09-15

fedortest[.]xyz 2019-07-12 2019-08-10

accounts.check-activity[.]com.ru 2019-08-02 2019-08-02

www.adservice.alexandr01299[.]xyz 2019-07-30 2019-07-30

www.alexandr01299[.]xyz 2019-07-30 2019-07-30

consent.alexandr01299[.]xyz 2019-07-30 2019-07-30

dokerest[.]xyz 2019-07-12 2019-07-27

dokertest[.]xyz 2019-07-12 2019-07-22

frostdank[.]com 2019-07-15 2019-07-16

frosdank[.]com 2019-07-15 2019-07-15

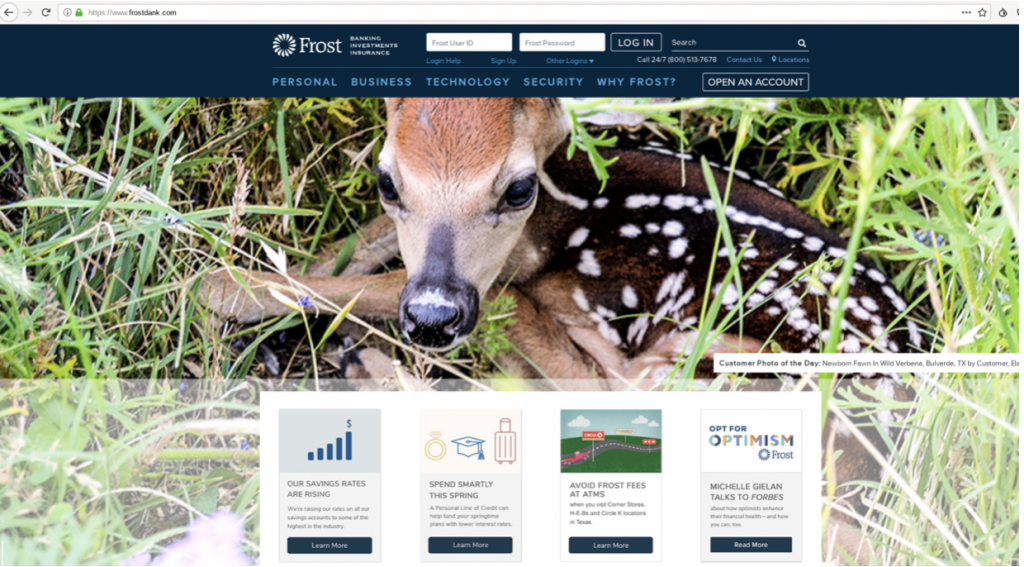

Some of these domains seem to be domains to test their attacks (like dokertest[.]xyz), but during the investigation, we discovered that frostdank[.]com was hosting a copy of the FrostBank website:

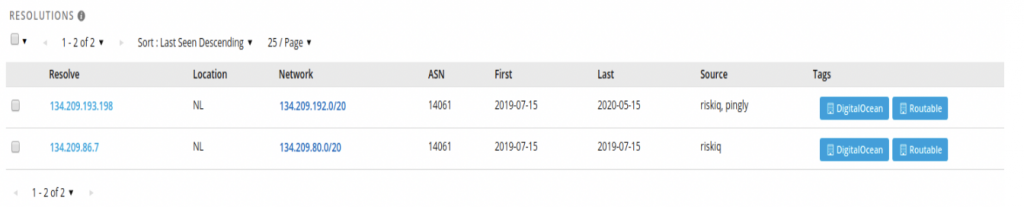

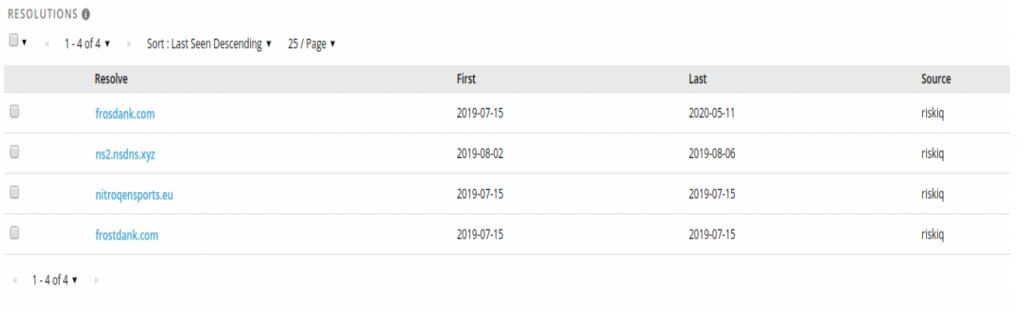

Searching more in that direction, we see that this domain was later hosted on a second Digital Ocean server, 134.209.193[.]198 :

This server was also hosting some suspicious domains likely related to this campaign, as they also impersonate bank domains.

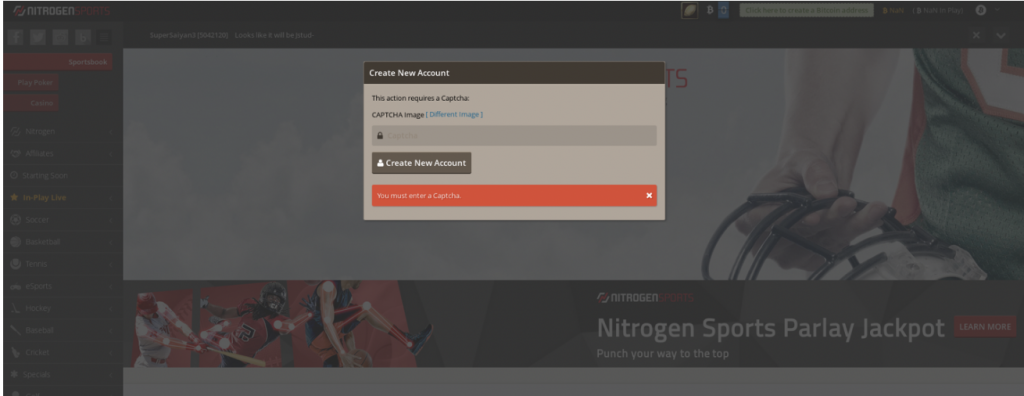

nitroqensports[.]eu is interesting, because even if it did not ring a bell at first, we realized that it was hosting a copy of nitrogensports.eu, an online sport gambling website in June 2019:

Seeing fake banks and online sport gambling website used in the campaign was a surprise to us, as we only saw fake email websites before, very likely used for digital surveillance. We think that this group may also have been involved in cyber-criminal activity, which would explain the banks and online gambling websites as targets.

We can summarize the links we found in a graph using Maltego:

All of these domains were registered between May and August 2019, so too recently to find anything interesting in Whois information, but the creation date we get in Whois confirms that it fits in the timeline of this campaign. It would be possible to have a more precise timeline of the utilization of these domains by looking at the certificates created for these domains on Certificate Transparency platforms such as censys.io or crt.sh.

Going further#

We have seen an example of how to use passive DNS to map an infrastructure. The example used here was a phishing attack, but the same technique can easily be used to map links between fake media running a coordinated disinformation campaign or to identify the owner of a website. If you want to go further on infrastructure analysis, you should become familiar with Certificate Transparency databases (like censys.io or crt.sh mentioned above) and also with how to identify shared analytic ids between websites (you can read this good Bellingcat article on this topic).

Have fun and stay safe!